Spending half of her life in China, Pearl S. Buck brought Chinese culture, society, and changing politics into the American conversation through her numerous novels set in the country. Even after the Communist takeover, Buck continued to work as an advocate for China, Taiwanese independence, and immigration issues. She used her platform as a writer to speak out against the atomic bomb and to promote civil rights, women’s rights, and disability rights as well changing laws that allowed Asian and mixed-race children to be adopted.

Throughout all of her activism, Buck was a prolific writer of biographies, novels, non-fiction, short stories, children’s books, and essays and articles about China and related issues. She won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1932, followed by the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1938, only the third American and the first American woman to do so, for her work depicting Chinese culture and her biographies. Today, she is remembered both in America and in China for her work bringing the two cultures closer together.

Early Life

Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker was born on June 26, 1882 in Hillsboro, West Virginia to Southern Presbyterian missionaries Absalom and Caroline Stulting Sydenstricker. Her parents had traveled to China as missionaries shortly after their marriage in 1880, and returned to the U.S. on furlough shortly before Pearl’s birth. She was born in the home that her maternal grandparents had built after coming to the U.S. as part of a group of Dutch settlers. Her mother had been born and grown up in the house while her father had grown up in the nearby town of Ronceverte, also to Dutch immigrants. Pearl was the fourth of her parents seven children and only had three surviving siblings.

Buck was only five months old when her parents resumed their missionary work in China, bringing their baby daughter with them. The family first lived in Huai’an for the first four years of Buck’s life. She grew up in the Chinese city of Zhenjiang (also known as Jingjiang and Tsingkiang) near Nanking along the Yangtze River, where the family moved in October 1892. Like her siblings, Pearl was tutored in English by her mother and was also taught to speak Chinese. Her father had spent many years translating the Bible into Chinese from Greek and was often away from the family doing missionary work in the countryside. Her mother was widely-traveled and enjoyed teaching her children world literature. In addition to learning from her Chinese tutor, she attended a girl’s boarding school.

When not at their primary residence in Zhenjiang, the family spent summers at a villa in Kulin on Mont Lu. Her father had built the stone villa himself in 1897 and would eventually die there in 1931. It was during the annual pilgrimages to this summer residence that Buck first decided to become a writer. Buck recalled her family being the minority in China with often few other white families in the area where her parents lived and worked as missionaries. She began to divide her life into two worlds, one she described as the “small, white, clean Presbyterian world of my parents” and the second the “big, loving, merry, not-too-clean Chinese world.” She noted there was often little overlap between these two worlds.

The Boxer Rebellion — which lasted from 1898 through 1901 — would deeply impact Pearl’s childhood. She and her family as well as many other Westerns living in China were completely deserted from Chinese residents they had counted as friends. The rebellion particularly impacted the Sydenstricker family as the movement was anti-Christian, anti-foreigner and anti-Imperialist. The family was forced to flee to Shanghai as a result of the rebellion, where they waited for news of their father, who had decided to remain feeling that no Chinese person would hurt him. The family returned to the U.S. in 1901 for home leave.

The family returned to China before 1907 and Pearl attended a girl’s boarding school in Shanghai for two years. Her parents had always treated the Chinese as equal and taught Pearl and her brother and sister to do the same. As a result, it was shocking to her to find the other girls at the Shanghai boarding school she attended often displayed racist attitudes toward the Chinese. Raised to speak Chinese as well as English, she was also dismayed to learn that most of her fellow white students only spoke English. During this time, she also volunteered for Door of Hope, an organization dedicated to helping child slaves and prostitutes in China.

Early Adulthood

When she was 19, Buck left China after being accepted to Randolph-Macon’s Women’s College in Lynchburg, Va. She graduated three years later in 1914 with honors and a degree in psychology. She wanted to remain in the U.S. but returned to China shortly after graduating as her mother had taken ill. She had not intended to return to China nor to follow her parents into mission work, but she took a job as a teacher for the Presbyterian Board of Missions in 1914.

While in China, she met a Cornell graduate named John Lossing Buck who was working as an agricultural economist. The two married in 1917 and Buck often served as a translator for her husband when they moved to the Anhui Province in rural Northern China. The region would inspire many of her future writings and would serve as the setting for her works The Good Earth and Sons.

The family returned to Nanking in 1920 due to the growing of political unrest and the May 4 Movement in China. Buck spent time teaching English and literature at the University of Nanking and the National Central University. In 1921, Buck gave birth to a daughter named Carol who was found to suffer from PKU and was severely mentally handicapped. A uterine tumor was discovered during delivery, requiring Buck to have a hysterectomy. Further stress was caused by the death of Buck’s mother from a tropical disease known as sprue. Her father would then move in with Buck and her husband after her mother’s death. The family returned to the U.S. in 1924 where Buck earned a degree in literature from Cornell and sought medical treatment for Carol. In 1925, she and her husband adopted a daughter named Janice.

The family returned to China in the autumn of 1925 after Janice’s adoption was finalized. However, unrest was growing in country as political tensions between the Nationlists and Communists reached a fever pitch. In 1927, the family was forced to evacuate with other Westerns as the result of the Nanking Incident, where several Westerns were murdered as the result of conflicts between Nationalists, Communists and Chinese warlords. As her father had refused to lave the city, the Buck family hid in the hut of a poor peasant family and were eventually rescued by American gunboats.

They lived briefly in Shanghai and then spent a year in Japan, where Buck began writing in earnest. Encouragement from her friends, including Chinese writers Xu Zhimo and Lin Yutang, encouraged Buck to pursue writing. She was also hoping a career could support her as her marriage was becoming strained. The family returned to Nanking in late 1927. Two years later, Buck again visited the U.S. hoping to find specialized care for Carole, ventually enrolling her in the Vineland Training School in New Jersey. Carol would live at the school for the rest of her life and Buck would serve on its board for the rest of hers.

Her marriage breaking apart, Buck met editor Richard J. Walsh who worked at John Day publishers in New York. He accepted her noevl East Wind: West Wind for publication. What began as a professional relationship would turn romantic. Her business in America settled, she returned to Nanking and began working on what would become The Good Earth in the attic of her home at the university. Buck also became involved in the relief campaigns for the victims of the 1931 China floods, writing a series of short stories detailing the struggles of refguees that were turned into radio plays in the U.S. These would later be published in her first short-story collection, The First Wife and Other Stories.

In 1932, the Buck family went to Ithaca, N.Y., and Buck accepted an invitation to a luncheon for Presbyterian women at the Hotel Astor in New York City. She gave a talk about how, while she invited the Chinese to share her Christian faith, she felt that China did nnot need the church and that missionaries were often ineffective because they didn’t bother to learn or understand Chinese culture, often trying to force their own culture on the Chinese along with their religion. The talk was published in Harper’s and scandalized the Prebyterian Board, forcing Buck to resign her position with them. The family was forced to leave China entirely in 1934. Buck anticipated she would return to the country, but the Communist takeover prevented this.

Writing Career

Buck divorced her first husband in 1935 after an unhappy, 18-year marriage and the same day her divorce was finalized married Richard Walsh, now president of the John Day Company that published her books. The couple settled into the Green Hills Farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania to be near to Walsh’s publishing house and the institution in New Jersey where Buck had committed her daughter Carol for medical care. Over the years, Buck and Walsh would adopt six more children, a son and a daughter. Buck’s daughter Janice would also take Walsh’s last name and live with the pair.

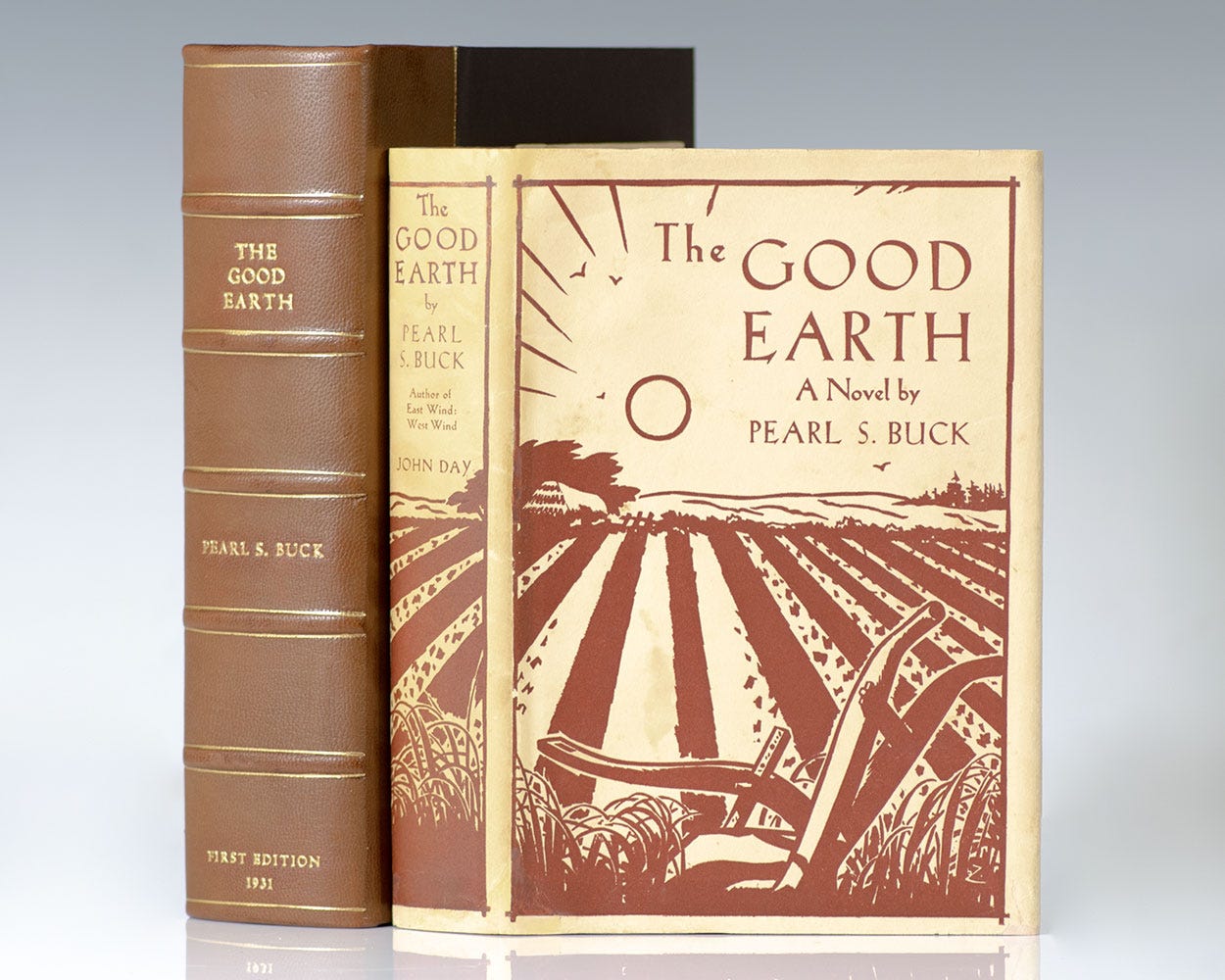

Buck had begun publishing her written work sporadically in the 1920s in magazines ranging from popular magazines such as the The Nation and The Atlantic Monthly to more locally focused magazines including The Chinese Recorder and Asia. When it was published in 1931, her novel The Good Earth gained international attention. The book would be a best-seller for two years and would sell 1.8 million copies in it’s first year of publications. In 1932, it was award the Pultizer Prize for the Novel and the Howells Medal for writing. The following year, she was inducted into the National Institute of Arts and Letters. She would follow The Good Earth with sequels Sons in 1933 and A House Divided in 1935. That same year, the three novels would be republished together in a single volume as The House of Earth trilogy. The Good Earth would be adapted into a film in 1937.

During this time, Buck also translated the Chinese classical prose epic Water Margin by Shui Hu Zhuan into English as All Men Are Brothers in 1933 as well as her novel The Mother, which was originally serialized in Cosmopolitan. Buck also wrote and published two biographies of her parents. The Exile: Portrait of An American Mother had originally been serialized in the Lady’s Home Companion but was then published as a novel in it’s own right in 1936. That same year, she would also publish Fighting Angel: Portrait of a Soul, a biography of her father who had died in 1931. The two books would be later combined into a single volume in 1944 as The Spirit and the Flesh.

In 1935, Buck would become the first female American and the third American ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Her Nobel lecture would focus on the Chinese novels she had read as a child and promote works such as the Chinese classics Romance of the Three Kingdoms, All Men Are Brothers, and Dream of the Red Chamber as works of international importance. Buck would not sit on her literary laurels, however, and would average one or two novels a year from 1938 through 1975, sometimes publishing under the pseudonym John Sedges. Her other major literary successes included Imperial Woman in 1956, Letters from Peking in 1957, Satan Never Sleeps in 1962, and The Living Reed in 1963. Most of these novels were set in China, though The Living Reed was set in Korea while her 1970 novel Mandala was set in India.

Over the course of her life, Buck would write three autobiographies, 43 novels, 20 works of non-fiction, 20 collections of short stories, and 20 works for children. At least one novel and several of her short stories would be published after her death. Her children’s novel, The Big Wave, also won the Bank Street Children's Book Committee's Josette Frank Award in 1948 for its depiction of a Japanese boy from a small fishing village rebuilding his life after a tsunami.

Activist and Humanitarian

After her return to the U.S., Buck became involved in a wide range of issues and efforts she tackled both in her novels and on the political frontlines. She fought against racism, anti-immigration sentiments, and misunderstood attitudes toward Asian cultures. Buck challenged racism in the American school system as well as discrimination against women, long before the Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s. Buck even spoke before many political leaders on these issues, leading the FBI to keep a detailed file on her to track any “anti-American activities” she might be engaged in.

In 1949, Buck was incensed to discover that adoption agencies would not accept Asian or mixed-race children, considering this children to be “unadoptable.” Buck founded Welcome House, Inc., an international, interracial adoption agency still in existence that has placed more than 5,000 children. She also found the Pearl S. Buck Foundation in 1964 to support children facing poverty and discrimination in Asia countries. She opened the Opportunity Center and Orphanage in South Korea in 1965, so following with branches in the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. During the late 1960s, Buck also traveled West Virginia to seek donations to preserve her childhood home in Hillsboro, which is a historic house museum and cultural center today.

In 1962, she urged President Kennedy to resolve the strained relationship between China and Taiwan by supporting Taiwanese independence during a visit to the White House. She became a well-known political activist and spokesperson for issues related to Asian culture, victims of the atomic bomb, international and interracial adoption, and the plight of children struck by poverty and war in Asia.

Buck was also a leading disability advocate well before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. One of her memoirs focused on raising a child with a disability, a topic that was not considered appropriate for polite conversation at the time. Her 1950 book The Child Who Never Grew was one of the first works by a prominent woman in American society talking about her experience with mothering an intellectually disabled child, the process of coming to terms with her daughter’s disability diagnosis, and the realization that her daughter also had talents and interets that still made her a unique individual rather than a diagnosis. Rather than pushing a narrative of self-sacrifice, Buck was determined to find a way to make a better life for her daughter and was horrified at the status of many institutions of the day before she found a place her child could thrive.

Later Life

After a series of strokes, Buck’s second husband and longtime publisher Richard Walsh died. She renewed a friendship at this time with William Ernest Hocking, who many of her friends felt did not have her best interests in mind. She quarreled with many friends and lost contact with others until Hocking’s death in 1966. Around that same time, Buck increasingly came under the influence of Theodore Harris, a former dance instruction. He took on a role as confidant and co-author as well as her financial needs.

Eventually, Harris was in control of all of her daily routines, her chairites, and was given a lifetime salary as head of Welcome House. He was accused of mismanaging the foundation, diverting large portions of donations to his own personal acccoutns and expenses as well as treating staff poorly. Before her death, Buck had signed over all of her personal possessions and foreign royalties to a foundation managed by Harris.

As an attempt to strengthen U.S. relations with China, President Richard Nixon was invited to visit the country in 1972. Nixon invited Buck to join him and several American dignitaries on the visit, but due to her anti-Imperalist opinions and depiction of the sharp, often cruel realities of peasant life in China, she was refused entrance to the country. Buck was even denounced as an “American cultural imperalist” by the wife of Chairman Mao. Buck was heartbroken by not being able to return to the land she had called home and loved for so many years.

Buck would die of lung cancer a year later on March 6, 1973 in Danby, Vermont. She bequeathed her manuscripts to both the Pearl S. Buck Birthplace Foundation in Hillsboro, West Virginia and the Lipscomb Library at Randolph-Macon Women’s College. Her tombstone is inscribed with her name in English as well as her Chinese name Sai Zhenzhju. The fact that she left three wills resulted in an ultimate three-way legal dispute over her estate between Harris, the Pearl Buck Foundation, and her seven adopted children. It was eventually settled in favor of her children with the foundation dropping their claims and the children giving Harris a financial settlement.

Buck’s life’s work live on not only through her writing but through the many organizations she founded. Many of the orphanages and adoption agencies she founded in Asia are still in operation and helping children today. She was honored in 1983 with a stamp as part of the U.S. Postal Service’s “Great Americans” series and then was inducted as a Women’s History Month Honoree by the National Women’s History Project in 1999. Today, Buck’s legacy is also preserved in China. The Zhenjiang Pearl S. Buck Research Association bears her name while her homes in Nanking and her summer villa in the Lushan Mountains have been preserved. The Pearl S. Buck Memorial Hall in South Korea was also named in honor of the writer.