The birthplace of the Renaissance, Florence is also the hometown of two of the most prominent writers Italy ever produced: Dante Alighieri and Giovanni Boccacio. At the same time, poet and philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli was writing his famous The Prince in honor of his de Medici patrons. It is perhaps the reputation of these writers along with the tradition of art, architecture, and culture that has drawn so many to Florence seeking inspiration.

Anglo-Italian writer and historian Harold Acton would be born in the city while numerous literary ex-pats would at some point call the city home, including Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Henry James, E.M. Forster, D.H. Lawrence, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Aldous Huxley, Mark Twain, Dylan Thomas, Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Fyodor Dostoevsky, George Eliot, Charles Dickens, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Today, the city still abounds with bookstores, libraries, and

Badia Fiorentina

Via del Proconsolo, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy

An abbey, church, and monastery, the Badia Fiorentina is one of the oldest religious sites in Florence and a great place to get a feel for the history of the city. It is also a site of historic literary importance because it was here that Dante met his muse Beatrice Portinari, daughter of Folco Portinari, as a child. According to some stories, Dante grew up in a home just up the street, and while his residence there is not confirmed, he likely would have known this church. It was also from this church that Boccaccio delivered his famous lectures on The Divine Comedy in 1373 from the chapel of Santo Stefano.

Founded as a Benedictine institution by Willa, Countess of Tuscany in 978 to honor her late husband Hubert, the building was one of the chief sites of medieval Florence. One of the major artistic patrons of the church was Willa and Hubert’s son Ugo, the “great baron” mentioned by Dante in his Divine Comedy. A hospital was added in 1071 and the church bell served as the city’s main timekeeper. It was rebuilt in the Gothic style between 1284 and 1310 and then underwent a Baroque transformation in 1627 and 1631.

Numerous artworks are also found at the church, donated to it by patrons over the years, though the famed Badia Polyptych by Giotto has since been moved to the Uffizi Gallery. The church was also used during World War II to hide and protect various valuable works of art. Visitors to the church today can still see works by Filippino Lippi, Giorgia Vasari, Mino da Fiesole, and early frescoes attributed to Nardo di Cione. Famed architect Bernardo Rossellino also designed the famed “cloister of the oranges” in the church, named for being the first attempt at creating an orangery in Florence.

Basilica di Santa Croce

Piazza di Santa Croce, 16, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy

Meaning “Basilica of the Holy Cross,” this Florentine church on the Piazza di Santa Croce is just south of the famed Duomo and was once marshland outside the city walls. An older building once stood on the site, but it was replaced between 1294 and 1442 with the current structure with gothic embellishments added in the 1860s. Filippo Brunelleschi was involved in finishing the church, which is why it also echoes the Duomo. Once the home of Franciscan friars, the church is now known more for who is buried here.

For more than 500 years, the church was the place to be buried or at least have a burial monument erected by the most wealthy and prominent families and people of Florence. Families like the Bardi and Peruzzi even paid to erect their own chapels in the church to ensure that they were commemorated here. Many of the funerary monuments in the church were created by some of the most prominent Florentine artists including Donatello, Andrea Orcagna, Giorgia Vasari.

While Dante died in exile in Ravenna, this church is where the main memorial to his life in Florence was erected. Famed writer and philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli is also buried in the church as are poet Giovanni Battista Niccolini and Vittorio Alfieri. Other notable burials in the church include Galileo, Leonardo da Vinci, Julie Clary Bonaparte, and Florence Nightingale as well as memorials to Guglielmo Marconi and Enrico Fermi, who are buried elsewhere.

Casa Guidi

Piazza San Felice, 8, 50125 Firenze FI, Italy

After their elopement, poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning moved to Florence for her health and also inspiration. Robert Browning did great amounts of research and used Italy and Florence in particular as a setting in his work while Barrett Browning wrote the 1851 poem Casa Guidi Windows about the house. It was in this home that their only child, Robert “Pen” Barrett Browning, was born, and where they gathered both members of the local literary and British ex-pat societies.

The suite of eight rooms is situated on the piano nobile or principal floor of the Palazzo Guidi, located opposite the south wing of the Pitti Palace, at Piazza San Felice. Originally built in the 1400s by the Ridolfi family, the building was originally two structures. It was the home of County Camillo Guidi, secretary of state for the Medici in 1618, from which it gets its name. The Guidi family would combine and refurbish the two buildings into a singular one in the late 1700s and then subdivided the home into apartments in the early 1840s.

The Brownings leased the apartment in 1847 and lived there for 14 years. In addition to Casa Guidi Windows, Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote Aurora Leigh while her husband produced Men and Women and began The Ring and the Book. Visitors to their apartment included the likes of Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Frederick Tennyson, William Wetmore Story, and Anthony Trollope and his wife.

The apartment remained in the family until Pen’s death in 1912, at which time it was given to the Browning Society in New York. They began restoration of the apartment then gave it to Eton College. It remains part of the Eton College Collections but is administered by the Landmark Trust. It is open to visitors Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays from April through November and is a residence for Eton students visiting Florence.

The Duomo

Piazza del Duomo, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy

Formally known as the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower) and as the Florence Cathedral, the Duomo is the masterpiece of the architect Brunelleschi and remains the largest masonry dome ever constructed. The cathedral complex is known as the Piazza del Duomo and is both a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the historic city center of Florence. Construction began in 1296 but was not completed until 1436 under the leadership of Coismo de Medici. Michaelangelo’s David and several sculptures by Donatello were commissioned for the church.

In addition to being the subject of numerous books itself as the dome changed architecture forever, the cathedral was and remains a must-stop for all visitors to Florence. The church was one of the highlights of the Baedeker guide to Florence, which was used both by those who came to visit Florence in reality and the characters of E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View, who use the guide to determine their travels. George Eliot’s historical novel Romola, set in Florence in the 1400s, also references the location among others in the Florence ruled by Lorenzo de Medici.

While the cathedral was built before Dante’s time, it is also home to the famed painting Domenico di Michelino, Dante, Florence and the Divine Comedy painted in 1465. Painted by the mysterious Michelino di Benedetto of whom no other works are known, the painting depicts the Florentine writer presenting his famous poem to the city of Florence with scenes from the work to his back. There are numerous other works of art located throughout the cathedral, perhaps of which is the cathedral itself laid together by hundreds of unknown stonemasons, glassmakers, and other artisans.

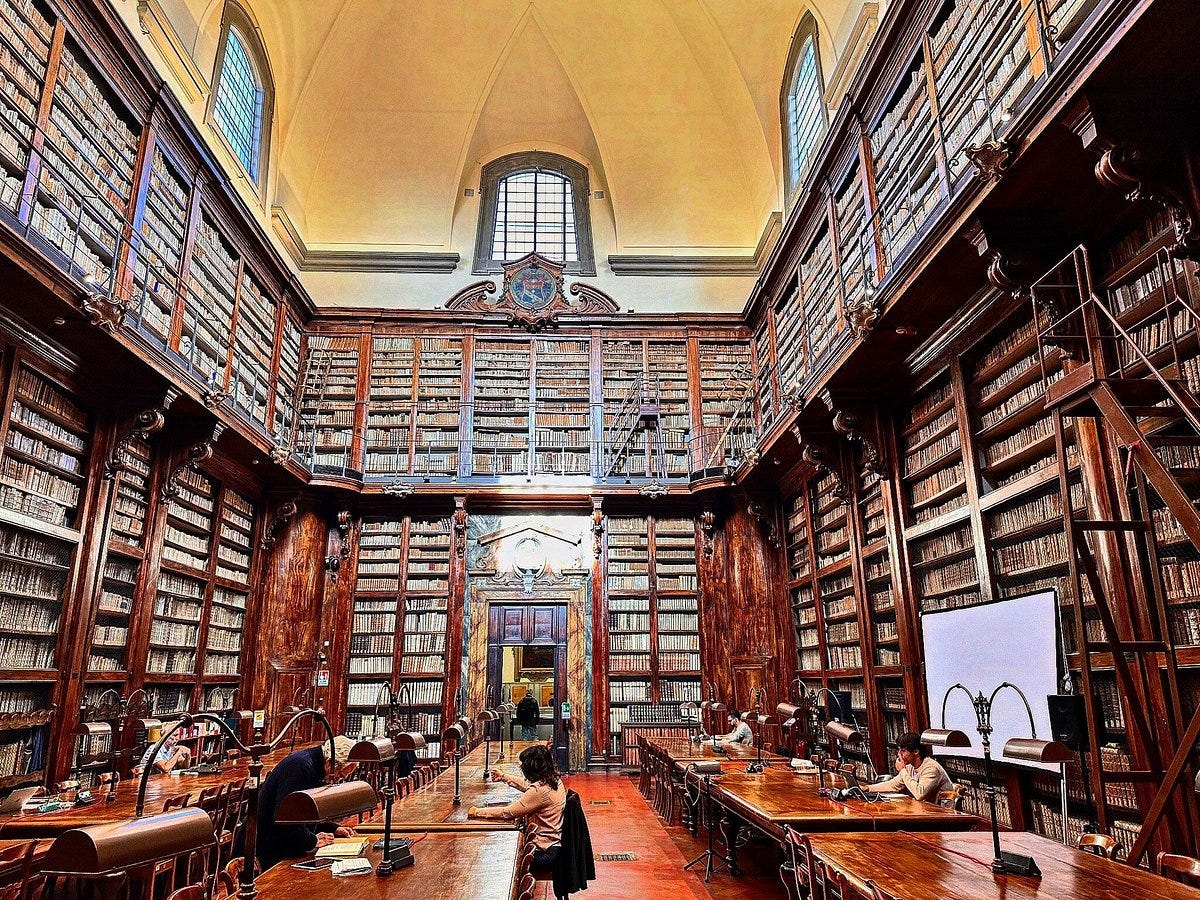

Florence National Central Library, the Laurentian Library, and The Marucelliana Library

Piazza dei Cavalleggeri, 1, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy; Piazza di San Lorenzo, 9, 50123 Firenze FI, Italy; and Via Camillo Cavour, 43, 50129 Firenze FI, Italy

Florence is home to three major libraries that are of major historical and national importance. The first of which is the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, or Florence National Central Library, which is the largest library in Italy, one of the public national libraries in Italy, and considered by many to be one of the most important libraires in Europe. It was founded in 1714 when scholar Antonio Magliabechi bequeathed his 30,000 volume collection to the city and by 1743, a copy of any book that was published in Tuscany was required to be deposited here. Originally known as the Magliabechiana, it was opened to the public in 1747. In the 1860s, it was combined with the Biblioteca Palatina Lorense and became a national library in 1885.

The main collections are held in a building along the Arno River in the quarter of Santa Croce where it was moved from its previous location at what is now the Uffizi Gallery. After a flood damaged more than a third of the library’s collections in 1966, a restoration center was established at the library first to restore its damaged artifacts and now to restore works from around Italy.

The library contains works that belonged to the personal collection of the de Medici family, original drawings of numerous monuments and buildings from around the city, a collectoin of works by Galileo, medieval medical texts and related preserved plant samples, and medieval manuscripts of the works of Dante, Giovanni Battista Caporali, Pietro Aretino, Romolo Ludovici, and others.

To date, the library is home to around 6 million printed volumes, more than 2.6 million pamphlets, 25,000 manuscripts, 4,000 incunabula, 29,000 editions of works from the 1500s or older, and more than 1,000 autographs. Artwork held in the library includes famous paintings of the Italian writers Petrarch, Jacopo Passavanti, Jacopo Sannazaro, and Niccolò Tommaseo.

Located in a cloister of the Basilica di San Lorenzo di Firenze was commissioned by the Medici Pope Clement VII to show the family’s transition from the merchant class to one of the job and ecclesiastical society. The library today contains many of the manuscripts and books belonging to the private library collection of the Medici family. The architecture of the building was designed by Michelangelo in the Mannerist style.

Commissioned in 1523, the library was constructed between 1525 and finally opened in 1571. Michelangelo himself left the city in 1534 and the rest of the construction had to be completed based on his plans. Scholars were allowed to access the library and Angelo Maria Bandini was appointed as the primary librarian in 1757, overseeing major additions to its collections. The famed reading room is still open to readers today by appointment.

The library is home to 11,000 manuscripts, 2,500 papyri, 43 ostraca, 566 incunabula, 1,681 sixteenth-century prints, and 126,527 prints of the seventeenth to twentieth centuries. Some of the most prominent items in the collection are the Nahuatl Florentine Codex, the Rabula Gospels, the Codex Amiatinus, the Squarcialupi Codex, A Latin Vulgate Bible, and the fragmentary Erinna papyrus that contains part of her Distaff.

Marucelliana Library or Biblioteca Marucelliana is another important public library in Florence, founded in 1752 when the will of Abbot Francesco Marucelli left the library to the people of the city. The library’s collection began as its own library and included numerous texts on Canon Law, of which Francesco was an expert. The library was expanded by his grandson and Angelo Maria Bandini, who also served as the head librarian of the Laurentian Library, did double duty as the first librarian here. It was here the first alphabetic catalog for a library was established.

In 1776, the suppression of the Jesuits brought even more collections into the library including a dozen manuscripts and prints. The library later purchased manuscript and literary collections from other prominent Florentines, including naturalist Antonio Cocchi and antiquarian Filippo Stosch. Even more collections were added over the course of the 1800s with English novelist George Gissing using the library as a center for his research during that time.

At present, the library’s collections include 490 incunabula, 7,995 cinquecentine, 2,927 manuscripts, and 69,345 personal letters and papers of interest, nearly 53,000 etchings, and 3,200 drawings from prior to the 1800s, and 9,000 librettos of melodramas, as well as numerous series of journals and newspapers.

Giulio Giannini e Figlio

Via dei Velluti, 1, 50125 Firenze FI, Italy

Anyone who wants to see how books were traditionally bound in Italy can go to the Piazza Pitti, also known as the Pitti Palace, to a sixth-generation family business that has been preserving Renaissance traditions since the 1800s. Located near the massive museum complex that the Piazza Pitti is today, Giulio Giannini e Figlio (Gulio, Giannini, and Figlio in English) was founded by Pietro Giannini in 1856 as a small shop. One of his major clients became the Grand Duke Leopold II who resided as the Palazzo Pitti nearby.

In the 1870s, the large English ex-patriate population of Florence began patronizing the bookbinding services of the company, leading it to focus more on that side of the business. A photo album and guest book kept by the family still records a number of prominent visitors who came to either check out the shop for themselves or purchase some of its goods.

Guido Giannini, Sr., who took over from his father Giulio, intensely researched medieveal and Renaissance bookbinding traditions when he took over the shop, helping preserve both historic manuscripts and creating new ones. He was an authority on the arts of bookbinding and printing, publishing several articles on the subject. He also created a collection of more than 1,000 bronze stamps for the leatherworking side of the business that are drawn from historical tools.

Since then, the families have developed a decoration of leather and parchment with gold leaf known as the “Florentine style” and have preserved the Renaissance or classical style of bookbinding and printing. Each new generation also adds to the skill and range that the shop offers with marbled paper and leather being one of the most recent specialties added to the shop’s repertoire. The shop expanded into stamping, leather desk sets, greeting cards, guest books, and a variety of created-to-order luxury goods that showcase the deep history of bookbinding and literature within the city.

Libreria Antiquaria Gozzini

Via Ricasoli, 49/103R, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy

Florence is home to a wide variety of bookstores catering to different tastes and readers in different languages, but one of the oldest and most interesting is the Gozzini Libreria Antiquaria, an antique and rare bookshop that has been operating in the city since 1850. While the store has traditionally specialized in books on the law and economics – two specialties of Florence itself – there are numerous other historic works and unique books for sale. The store also has some more modern titles as well.

Oreste Gozzini originally opened a small book-buying business on the Piazza del Duomo in 1850 under the name “Libreria Dante.” After fighting in the Third Italian War of Independence in the 1860s, Gozzini returned to Florence and moved the shop to the Via San Egidio. By the 1880s, the business had grown to the point he opened a second branch in Rome. His son Gino inherited the store, moving it around several times as the store’s inventory grew and eventually settling on the famous Via Ricasoli, once known for being the main center of bookstores in the city. The store was originally at No. 28, but in 1958 moved to its present location at No. 49, where it remains today.

Gino left the business to his son-in-law Renato Chellini, whose son Pietro joined him in the family business in 1950. His son and grandson, Francesco and Edoardo Chellini, continue to run the store, the fifth and sixth generations to do so. The small windows overlooking the Palazzo Alfani belie more than 20 rooms filled with antique books and furniture with distinguished figures of Italian legal and economic history often frequenting the bookstore in the 1900s to look for obscure and important texts.

In 1998, the shop began its “virtual bookshop” and today sells more than 82,000 volumes online. Paper files and digital databases sort books by type, period, and price. The store also offers traditional prints and engravings and has a YouTube channel that talks about some of his rare acquisitions, techniques for preserving historic books, identifying when they were bound, and tours of its special collection rooms. The shop is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers.

Museo Casa di Dante

Via Santa Margherita, 1, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy

Established in 1965, the Dante House Museum as it’s known in English, is likely not the site where the poet lived though it is approximately there. Little of the original area remains, but the museum preserves much of what life would have been linke for Dante when he lived in Florence. The museum was created as a tribute to the most famous poet to come from the city on the 700th anniversary of his birth and provides insight into both Dante’s life as well as medieval Florence.

Historians do know that the Alighieri family lived somewhere between the church and the Piazza dei Dontai in the 1200s. The house museum that exists today was constructed on an available site in that area using techniques and styles that were prominent in Florence at the time, based on historical documentation. It is known the family lived in Florence as far back as the 1100s though they claimed to have lived in the area since the ancient Roman Empire. Dante was exiled from his beloved Florence in 1301 due to ongoing political strife and died in Ravenna, having never been allowed to return home.

Visitors follow a route through the museum that highlight key moments in Dante’s life and how they influenced his poetry. There are also reconstructions of every day items and clothing that would have been commonly known to Dante and other Florentines of the period between 1265 and 1321 when he lived. The first floor includes documents that show Dante’s baptism, public life, election to office as prior of the town, and his participation in local military and political struggles as well as weapons used at the time. The second floor demonstrates his exile and the third has the various iconography and work of Dante over the centuries.

Since 2020, the museum has incorporated more technology into its exhibits with a multimedia set up that allows visitors to have a more interactive experience with Dante and his works. Additionally, the museum also offers online tours, workshops, guided tours, and tours in period costume to help visitors step back in time with the Supreme Poet. The museum has been maintained by the Unione Fiorentina since they were commissioned to create it in the 1960s.

Piazza Della Signoria

P.za della Signoria, 50122 Firenze FI, Italy

Located in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, the Palazzo della Signoria is the birthplace of the Florentine Republic and still serves as the heart of city politics. It has long been a major meeting place for locals and tourists because of its proximity to the Piazza del Duomo and its Uffizi Gallery. In 1982, it was included as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site declared as Florence’s Historic Center. The Palazzo Vecchio or “Old Palace” served as the city hall to this day. It was originally the palace of the Medici Dukes, but they donated to the city when they moved across the Arno to the Palazzo Pitti.

Excavations at the site have shown it was occupied as far back as the Neolithic though square began to look as it does now in the 1200s when the victorious Ghibellines began pulling down the homes of the defeated Guelphs. It was here that the followers of Savonarola carried out the famous Bonfire of the Vanities, which included the burning of any works of art, literature, music, or goods deemed sinful. It remains one of the most well-known public book burnings and acts of censorship in history.

Savonarola was later hung as a heretic in the same square. Several works of historical fiction have referenced this event including George Eliot’s Romola, E.R. Eddison’s A Fish Dinner in Memison, Irving Stone’s The Agony and the Ecstasy, Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, and as the title for Tom Wolfe’s 1987 novel of the same name. In E.M. Forster’s A Room With A View, the location is one of several in the guidebook that the protagonist visits and the knife fight scene in the 1985 film version of the movie was also shot in the piazza.

The Medici patronage of the arts saw numerous famous sculptures located to the plaza, making it a major tourist attraction in later years. Works like Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus, Ammannati’s Nettuno, Donatello’s Judith and Holofernes and the equestrian statue of Cosimo I by Giambologna all stand here. This was also the original location of Michelangelo’s David, which has since been moved into safer quarters. The nearby Loggia dei Lanzi houses Cellini’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa, Giambologna’s Abudction of the Sabine Women, and the Medici lions.

Piazza di Santa Maria Novella

Piazza di Santa Maria Novella, 50123 Firenze FI, Italy

One of the main public squares in Florence, the Piazza di Santa Maria Novello is the location of the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, the National Museum of Alinari of Photography, and the Grand Hotel Minerva, among other sites. In addition to its name after the prominent church, the plaza was often called the Piazza degli Stranieri or “Plaza of Foreigners” because it was a popular place for the many ex-pats living in the city to gather. The writer Henry James was also known to visit the plaza and write there when he was working on his novel Roderick Hudson. It was at the Grand Hotel Minera that the writer Henry Wadsworth Longfellow stayed in Florence and in the piazza that he worked on his English translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

The Grand Hotel Minvera itself is located on the site where monks of the church were originally held. It was later bought by several aristocratic Florentine families, who built the 1300s palazzo that stands today. By the 1800s, the home was converted into a hotel for travelers but received its modern transformation in the 1950s by two prominent Florentine architects. Several of the features of the hotel, such as its wooden beams, date back to medieval times. A plague on the hotel notes Longfellow’s stay at the piazza and the area’s reputation as a gathering place for foreign travelers.

Longfellow may have also taken inspiration from the frescoes inside the Santa Maria Novella by Nardo di Cione that depict the scenes of the Last Judgement and Hell taken from Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Cappella Strozzi di Mantova of the church. The works were commissioned by the powerful Strozzi family with Andrea di Cione, better known as Orcagna, doing the frescoed altarpiece in the church. Artworks by Botticelli, Brunelleschi, Lippi, Pisano, and others also decorate the church.

The church itself the first great basilica church in Florence and the principal Dominican church in the city. Consecrated in 1420, it is a real contrast to the 1930s remodel of the train station that took its name. Many visitors come to see the master frescoes done by Gothic and early Renaissance artists in honor of the famed Florentine families who were buried in the church crypt. Fans of Boccacio will know the church for its prominent role in The Decameron.

It is from this location that principal group of seven young women and three young men of Florence gather before they flee the city as the Black Death takes hold. Poignantly, the group leaves from underneath the frescoe of Dante at the Cappella Strozzi di Mantova. As they head into the countryside, they tell a story each night with the resulting frame story producing 100 stories each. The work itself shows the impact of Dante on literature of th period as well as medieval senses of religion, fortune, and culture. Some of the characters are based on real life people while others are based on stories and fables that would have been common at the time.

The anti-clerical stance of the book made it one of the sinful works of literature burned in the Bonfire of the Vanities and it was among the most well-known books to be included in the fire. The book would also be censored by several popes. However, the work helped launch literature of the Renaissance across Europe and catapulted Boccacio, along with Dante and Petrarch, into the status of one of the “Three Crowns” of Italian literature. Built between 1276 and 1420, the church from which Boccacio’s pilgrims fled has stained glass windows dating back to the 1300s and contains the famous pulpit from which Father Tomaso Caccini denounced Galileo.

Firenze Santa Maria Novella

Piazza della Stazione, 50123 Firenze FI, Italy

A railway station built in 1848 and remodeled in 1934 might seem an odd literary site, especially since it is sometimes considered a modernist eyesore when compared to the nearby Gothic Church of Santa Maria Novella for which it is named. In this case, the station is highly important for what once stood here as well as its role in the 1966 flood of the Arno, though there are numerous figures who probably made their way through the famous station.

Long before the train station existed, the Via Valfonda extended where it is located now. On that road was once the Palazzo Marini, a boarding house run by a French woman. It was here that Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley came when they arrived in Florence in 1819. It was also at this house that Mary Shelley gave birth to a son they named Percy Florence Shelley, the only one of their four children to survive to adulthood. The couple remained in the home through the winter and were stunned to find how cold it could get in Florence.

It was in this house that Percy Shelley wrote his Ode to the West Wind and often wrote about how Florence in particular was a “paradise of exiles” and “retreat of pariahs.” Mary also wrote a great deal during this time period, the act of writing helping to soothe her depression from losing two children in Venice the year before. A plaque now stands at the approximate location of the boarding house where the couple stayed on their sojourn to Florence.

In 1966, the boiler room of the train station was also used to preserve, wash, and dry manuscripts from the National Central Library that had been damaged in the floods. This helped preserve many valuable documents that might have also been lost. Those who go into the train station might want to pay respects also to the memorial erected at Platform 16, honoring the memory of the Italian Jews who were deported to Nazi concentration camps from this station during World War II.

Ponte Vecchio

Ponte Vecchio, 50125 Firenze FI, Italy

Meaning “the Old Bridge” this medieval stone bridge over the River Arno is the only one of the ancient bridges of the city that was not destroyed during World War II. The bridge has played a central role in the road system of Florence, and the original bridge on the site was believed to have been commissioned by the Emperor Hadrian in 123. Whiel closed to vehicular traffic today, the pedestrian bridge connects many of the important tourist locations in Florence including the Piazza del Duomo, the Piazza della Signoria, and the Palazzo Pitti.

The Roman bridge was destroyed in a flood in 1117 and reconstructed in stone. It was again swept away by floods in 1333, though its two central piers remained. The bridge in its current form was rebuilt in 1345. There is a lot of evidence that the bridge marks the earliest location where the Arno was crossed in Florence and is mentioned in numerous historical and artistic accounts of the city throughout the ages. The bridge began a renovation project in 2024 to help restore and straighten the medieval stones.

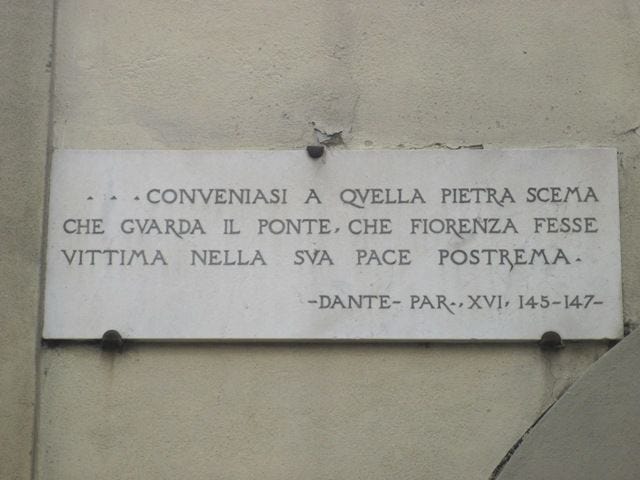

The bridge appears in many works of literature because of its status as an important Florentine landmark. Perhaps one of the earliest literary references to it coms in Dante’s Paradiso, which records how the bridge was the location of the murder of Buondelmonte de’ Buondelmonti, the event that incited the fighting between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. There is a plaque on the bridge that marks this spot and quotes Dante about the event.

Likewise, George Eliot referenced this event and location in her Romola, which is set at the same time as Dante was alive. A major tourist attraction in the 1800s, the bridge also features as one of the locations the British tourists visit in E.M. Forster’s Room with a View and was likely visited by Forster himself when he took his own trip to Florence that served as inspiration for the book.

32 Via de’Bardi

Via de' Bardi, 32, 50125 Firenze FI, Italy

The Via de’ Bardi in Florence has been home to numerous historic events and important people in the city’s history. Originally a home to many of the city’s impoverished residents, the powerful Bardi family took over the street in the late 1200s and early 1300s, giving it its current name. After a building collapse, Cosimo de Medici prohibited building on that side of the road and a plaque still stands commemorating the event. The street is also the first place St. Francis of Assisi allegedly stopped when he visited the street with other famous residents including writers Giovanni Papini at No. 12 and Francesco Redi at No. 16.

However, it was No. 32 that particularly appealed to English-born writers living in Florence. It was this address that George Eliot gave to her protagonist and novel’s namesake Romola, who lives at this address with her blind scholar father Bardo de’ Bardi. While Eliot herself first stayed at 13 Via Tornabuoni - then the Pension Suisse - and then took up residence at 10 Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci - then the Hotel della Vittoria - another English writer would actually move into the residence at No. 32.

Perhaps it was because of the address’ mention in Romola that D.H. Lawrence chose this address to stay at during his second visit to Florence. During his first visit in 1919, Lawrence stated at the Pension Balestra at 5 Piazza Mentana, now known as the Hotel Balestra. He described this location in depth in his novel Aaron’s Rod. When he came for a second visit in 1922, he stayed at this house. The third time Lawrence came to Florence he didn’t stay in the city but outside it at the Villa Merenda where he wrote his controversial Lady Chatterlay’s Lover.

Locally, No. 32 is part of the larger Canigiani Palace, a building constructed by the Bardi Family in the 1300s. The palace gained its current name after the family went bankrupt and it was sold to Giovanni di Antonio Canigiani in 1469. It was one of several previous porperties owned by the Bardis that Canigiani acquired in the wake of their downfall, and it remained in his family. Potentially, the famed writer Petrarch’s mother grew up in the house as she was a member of the Canigiani family.

Villa Brichieri Colombi

Via di Bellosguardo, 20-22, 50124 Firenze FI, Italy

The name Bellosguardo means “beautiful view” because this street is known to have some of the most beautiful views of the city center of Florence. This is probably why numerous homes were built off the road on the hill so that this view could be better admired. The street was very popular with ex-patriates living in Florence. It was here that Florence Nightingale was born at the Villa La Colombaia and named for the city below. Hawthorne stayed at the Villa Montauto and the Villa Castellani, now known as the Villa Mercedes, which inspired his The Marble Faun.

However, everyone knew the best view was from the Villa Brichieri-Columbi, which has been owned by a series of literary women from outside Italy. One of its first notable owners was the English novelist, speaker and poet Isabella “Isa” Balgden, who was born in India and allegedly of Swiss nationality but believed to be the daughter of an English father and an Indian mother. She and her home at Villa Brichieri-Columbi became the center of English literary society in Florence. After her arrival in Florence in 1850, she was frequently visited by Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Nathaniel Hawthorne, the Trollopes, and Robert Bulwer-Lytton, son of the novelist. Elizabeth Barrett Browning so admired the view that she put references to it in her Aurora Leigh.

She would sell the villa to Constance Fenimore Woolson, the American novelist, poet, and short story writer who was also the grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper. Shortly after she took the lease to the house in 1886, she was joined by her friend – and some speculate even more intimate friend – the writer Henry James. He lived on the first floor apartment and she on the second with the home again becoming a center of literary gatherings in Florence. James wrote most of his novel The Aspern Papers while living at the house.

Today, the home is the private residence of the American artist and poet Caroline Burton, who occasionally invites a few visitors to come see the house and its views. A plaque quoting Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s impression of the home in her poetry has been erected on the site, honoring its contribution to literature and its role as a gathering point for generations of literati.

Villa La Pietra

Via Bolognese 120, NYU Florence, Via Bolognese, 120, 50139 Firenze FI, Italy

One of the many Renaissance era villas that eventually became the home of ex-patriates in the city, the Villa La Pietra was bought and modified by the banker Francesco Sassetti in 1460. It was sold to the Capponi family in 1545 and then came into the hands of Cardinal Luigi Capponi, who gave the structure its current baroque exterior. From 1865 to 1871 when Florence was briefly the Italian capital, it was the home of the Prussian Embassy.

In 1903, the home came into the possession of Arthur Acton, an art dealer who was the illegitimate son of a British diplomat living in Egypt and his Neapolitan mistress. Acton began leasing the home with funds from his marriage to the American heiress Hortense Mitchell and eventually purchased it outright in 1907. The villa became the home for the couple’s impressive art collection and they laid out the formal gardens to house numerous statues they had acquired.

It was also in this home that their son, the writer, scholar and aesthete Sir Harold Acton was born in 1904. One of the principal members of the British Bohemian group from the Roaring Twenties known as the Bright Young Things, Acton would count among his friends the writers Nancy Mitford, Anthony Powell, Henry Green, Dorothy Sayers, Evelyn Waugh, and John Betjeman. Acton would co-found the avant-garde magazine The Oxford Broom, be the model for Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited, and published a groundbreaking, three-volume study of the Medicis and the Bourbons between the two world wars.

Acton lived at the villa until 1913 when he was sent to England for school, eventually attending Eton alongside figures like George Orwell, Ian Fleming, Anthony Powell, and Henry Green. While he didn’t return to his childhood home until after World War II, he restored it to its former glory as it had largely been decimated by German soldiers. As his older brother died in 1945, Acton was the sole heir to the house and left it in his will to New York University in 1994. The villa is now home to NYU Florence, which hosts study-abroad students from around the world.

Great piece!