It covers more than 70% of the earth’s surface and is home to 94% of the world’s wildlife. We have only explored 5% of its contents and it contains entire mountain ranges, volcanoes, and more historical artifacts than housed in all the world’s museums combined. Our oceans are one of the most amazing and integral parts of our planet, and yet what we don’t know about them far exceeds that which we do.

To bring more attention to this important facet of our planet, the role it has in supporting humanity, and the dangers it faces because of climate change and pollution, National Oceans Month has been celebrated every year since 2005 in America. Additionally, June 8 marks World Oceans Day as recognized by the United Nations since 2008. By working together to sustainability manage our oceans, we can continue to enjoy the sea’s natural wonders as well as the many resources it provides us.

CURRENT

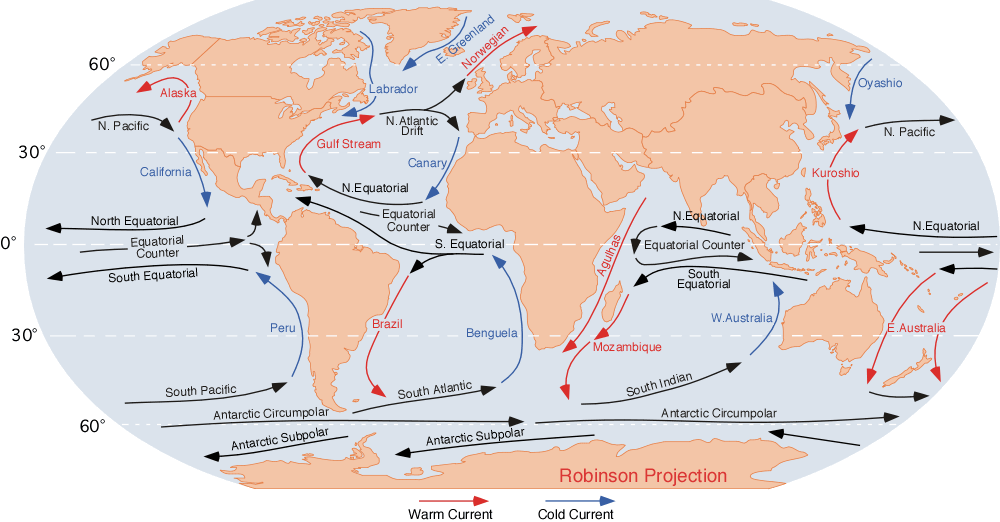

Literally the motion of the ocean, a current is defined as the directed movement of seawater caused by a number of forces including wind, waves, cabbelling, temperature, salinity, and the Coriolis effect. Ocean currents play important roles in the climate of the earth and influencing weather patterns the world over. Perhaps the Gulf Stream is the most famous current though it is one of dozens of currents - both warm and cold - that circulate throughout the planet. The study of currents impact much from fish migration to marine habitats to weather events that there is even a study of currents: currentology.

The word current comes from the Proto-Indo European root word kers- meaning “to run.” This evolved into the Latin currere meaning “to run, move, quickly.” From there, the word entered old French as the word corre meaning “to run” and the term corant meaning “running, lively, eager, swift.” The term originally entered English spelled as curraunt around 1300, meaning “running, flowing, moving along. It wasn’t until the mid-1400s that the meaning of “presently in effect” was added to its definition with the term currency referring to the flow of money in the late 1400s, the phrase current events from 1795, and current affairs from 1776.

Currents are created by three main factors, according to the National Ocean Service. The first is the rise and fall of tides, which are strongest near the shoreline. These tidal currents are very regular and can often be predicted, which is why it can be estimated when high tide and low tide will take place. Wind is the second factor that drives currents. Localized wind can direct coastal currents and create phenomena like coastal upswelling where cold water rises atop hot water. On a more global basis, wind drives currents on the open ocean allowing water to circulate for thousands of miles slower than tidal or surface currents.

The final factor driving currents is a process known as thermohaline circulation where density differences between the water’s temperature and salinity vary throughout the ocean. This process can happen both in deep and shallow areas of the ocean. global conveyor belt created by thermohaline circulation is the reason why Europe is more temperate than other regions of the same latitude while tropical conditions exist in other parts of the world. Beyond weather and climate, ocean life can also rely on currents for transportation and as a food source.

Plankton are often brought into areas through cold water currents in polar and subpolar regions and their place as a vital part of the ocean food chain means that many ocean creatures would starve without this movement. Sharks, whales, and sea turtles often rely on ocean currents for quick travel between feeding and breeding grounds. Jellyfish are also known to utilize currents as a way to find new sources of foods. Currents are also instrumental in the life cycles of numerous sea creatures, like the European eel.

Knowledge of currents and how they work has long been an important factor in the shipping industry. By knowing which way the wind is blowing, shipping companies can reduce fuel costs and build or maintain speed - something that was especially vital during times when ships out at sea could spend months without contact with other human beings. It was Juan Ponce de Leon who first reported the Gulf Stream to Europeans in 1512. The use of the Gulf Stream allowed Spanish ships to sail from the Caribbean to Spain quickly and helped drive their cultural dominance of the region.

Benjamin Franklin was also intrigued by the Gulf Stream when he worked for the Colonial Board of Customs in England. Sailors were complaining that it often took longer for a ship to sail from Cornwall to New York than from London to Rhode Island, despite the distance between Cornwall and New York being closer on the map. Franklin interviewed whaling captains who told him of a section of the ocean marked by color changes, warm winds, and whales that made traveling to Rhode Island quicker.

The Gulf Stream is known today to behave an important role impacting the climates of Florida, Ireland, western Great Britain, the western coastal islands of Scotland and northern Norway. Additionally, the great oceanic biodiversity found around Nantucket, Mass., is accredited to the community’s location along the Gulf Stream. One of the downsides is that the Gulf Stream’s warm water and temperature often increase the intensity of cyclones, tropical storms, and hurricanes in the region.

Why do some currents go in some directions and other currents go the opposite way? You can thank the Coriolis effect, which is the reason currents are counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. The Coriolis effect is created by the rotation of the earth and has implications for everything from how balls bounce to which way water drains in a sink to how hurricanes and cyclones move across the ocean.

KELP

A type of large, brown algae seaweeds, there are 30 species of kelp that create massive underwater forests in the ocean that serve as homes and food sources for animals, plants, and people. While it can give a plantlike appearance, kelp is technically classified as a heterokont because of how its tissue is constructed. Kelp has long been an important resource for those living in the ocean and beside it.

While there is evidence that humans were utilizing kelp as far back as the Middle Stone age, the word kelp is a fairly vague term in the English language. Its specific origins are not known, but it is known that the Middle English term culpe was being used in the late 1300s. By the 1660s, this became the term kelp meaning “large seaweed.” By 1834, the term kelp applied only to a type of seaweed in the Pacific Ocean off the American coast while the slang term Kelper appeared in reference to residents of the Falkland Islands by 1896. While some might think that the word kelp has some connection to the mystical Scottish water demon known as a kelpie, that word actually has its roots in the Gaelic terms calpa or cailpeach meaning “heifer or colt.” The spelling as kelpie first appeared in the 1750s though similarly spelled place names in Scotland are older.

While not one of the most diverse types of marine algae out there, kelps are a vital part of the ocean ecosystem with kelp forests making up important coastal habitats. Kelp forests and smaller groups known as kelp beds serve as food and shelter for species including rockfish, amphipods, shrimp, marine snails, bristle worms, and brittle stars. Marine mammals and birds that eat these animals - such as seals, sea lions, whales, sea otters, gulls, terns, snow egrets, great blue herons, cormorants, and shore birds - can also often be found lurking around kelp forests for their next meal.

Found primarily in temperate and arctic waters, kelp has a similar structure to that of a forest with several layers from the seafloor and coral reefs up to the kelp canopy where the largest species grow and float. To the untrained eye, kelp may seem like a simple organism, but they actually serve as complex ecosystem engineers and brings in a diversity of species to their location. Kelp forests are often located in nutrient-rich areas of the ocean and some species grow perennially with die-backs during times when nutrients are less available.

Humans have also had a long relationship with kelp and kelp forests. There is evidence that humans in South Africa during the Middle Stone Age harvested kelp along with abalone, limpets, and mussels to supplement their diets. There is also one theory that following the harvests of kelp forests around the Pacific Rim was a factor in bringing humans from Northeast Asia into the Americas. Kelp remains an important ingredient in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Russian Far East cuisine and has also been cultivated by humans to bring other edible sealife into an area.

Humans have also had a long relationship with kelp and kelp forests. There is evidence that humans in South Africa during the Middle Stone Age harvested kelp along with abalone, limpets, and mussels to supplement their diets. There is also one theory that following the harvests of kelp forests around the Pacific Rim was a factor in bringing humans from Northeast Asia into the Americas. Kelp remains an important ingredient in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Russian Far East cuisine and has also been cultivated by humans to bring other edible sealife into an area.

Outside of its dietary use, kelp has been used commercially to make soap and glass. The rich iodine and alkali produced in burnt kelp - known as kelp ash - was used to produce sodium carbonate. Kelp was also one of the few commercial sources of iodine during this period. Following the Highland Clearances, kelp ash production became a vital lifeline for poor families until a collapse in the kelp market in the 1820s led to its general demise by the 1840s. Other commercial uses for kelp include the use of kelp-derived carbohydrate alginate to thicken products running from ice cream to jelly to salad dressing to toothpaste and dog food as well as in dentistry and orthodontics.

Much like forests on land, kelp forests are also facing a decline due to overfishing, pollution, climate change, and invasive species. Overfishing can reduce the number of predator animals that eat the fish that consume kelp. As a result, the kelp forests are diminished. Kelp is also sensitive to pollution and temperature changes, meaning that kelp forests can die off easily if the right environmental conditions are not met.

An estimated 95% of kelp forests off the coast of California have disappeared due to rising ocean temperatures in the past decade alone. The result has been that sealife relying on these kelp forests is in decline as well. In order to maintain oceanic biodiversity, work is being done to restore kelp forests in coastal areas with harvests of both kelp and the creatures that rely on them being restricted. Educating the public about the importance of kelp in the ocean ecosystem. The kelp forest exhibit at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California gives visitors a unique chance to step into a kelp forest and see just how vital these algae area.

MARINE

Marine regions cover three-fourths of the earth’s surface, including oceans, coral reefs, and estuaries. Marine life depends on the saltwater habitat of the marine biome and unlike terrestrial habitats, marine habits are shifting and ever-changing. In order to understand this changing environment, the study of marine biology studies both the vast types of life and habitats found in the sea from those along the shoreline and in coastal areas into the deepest zones of the ocean. Marine life provides food, medicine, raw materials, as well as recreation and tourism throughout the planet, making the study of it essential to the way we live.

The word marine has its roots in the PIE root word mori meaning “body of water,” which evolved into the Latin word mare meaning “sea, the sea, seawater.” A form of this word was the Latin marinus meaning “of the sea.” This was translated into Old French as the term marin meaning “of the sea, maritime.” By the late 1300s, the noun marine meaning “seacoast” had entered the English language with the adjective form appearing around the mid-1400s.

By the 1660s, the term marine had come to refer to the collective shipping of a country and by the 1670s it referred specifically to a type of soldier serving on a ship. Related and of similar origins is the adjective maritime, which comes from the Latin word mare and its form maritimus meaning "of or near the sea." This word also entered Old French as maritime in the 1500s and then first entered English as meaning “pertaining to the sea” in the 1540s. It began to refer also to the seacoast regions of a country by the 1590s.

Humanity has long been fascinated with the ocean and marine life. The ancient Greeks and Phoenicians were among some of the first explorers of both the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and as a result began to learn about tides, fossil remains of shellfish, and the classification of marine animals. In his classification of animals, Aristotle was one of the first to recognize the difference between sea creatures and land creatures as well as the first to describe how these animals looked and seemed to move through their life cycles.

Meanwhile across the world, the ancient Polynesian cultures were also exploring marine life and the science of the sea. Major explorations of the Pacific by Polynesian explorers took place between 300 and 1275 CE, seeing the expansion of Polynesian cultures throughout the Polynesian triangle. They developed new and unique ways of both understanding and managing marine life for their own benefit as well as were some of the first to explore the deeper oceans before the Age of Discovery launched in Europe.

From the late 1700s until the 1900s, the voyages of James Cook on the HMS Endeavor, Charles Darwin on The Beagle, and Charles Wyville Thomson’s HMS Challenger brought back numerous marine specimens and helped influence others to take a deeper look at what the ocean had to offer. The USS Albatross was the first research vessel built purposefully for marine research and cleared the way for the modern study of marine biology. The first marine labs began to appear in the 1960s and 1970s and as technology increased, researchers could delve deeper and deeper into the sea through submersibles and remotely operated underwater vehicles.

Just like above the surface, there are numerous specific habitats and biomes found within the ocean itself. While seawater is common to all these habitats, they can be further defined based on factors such as temperature, sunlight, nutrients, salinity, dissolved gasses, acidity, turbulence of ocean waves, distance from the sea bottom, substrate, and whether there are organisms like kelp, coral, mangroves, and seagrasses that encourage other animals and plants to thrive in the area.

There are four main categories of marine habitats and ecosystems: coastal, surface water, open ocean, and sea floor. Within each of these habitats are further smaller ecosystems that are shaped by a variety of different factors and are home to different types of life. Closer to the land are intertidal zones, sandy shores, rocky shores, mudflats, mangrove forests and salt marshes, estuaries, kelp forests, seagrass meadows, and reefs. In the deeper surface waters are the surface microlayer toward the top and the epipelagic zone about 200 meters down. In the open ocean or deep sea starts where sunlight begins to lose its energy in the water.

As a result, this is where a variety of bioluminescent creatures begin to dwell. This area can be further divided into the mesopelagic, bathypelagic, abyssopelagic, and hadalpelagic zones. On the sea floor or the benthic zone, life revolves around vents and seeps, trenches, and seamounts. The knowledge of marine life decreases the closer to the sea floor.

OCEAN

Home to 97% of the planet’s water, the ocean is integral to life on earth both in terms as a resource for food and materials as well as its influence on weather and climate. In addition to serving as a climate regulator for the planet, the ocean has long provided humans with a means to connect via trade and travel. However, human actions haven’t always been beneficial to the ocean in return with pollution, overfishing, and numerous other environmental threats putting both the ocean and the planet itself in danger.

The origin of the word ocean comes from an ancient Greek god, though etymologists are unclear how that name itself evolved. Oceanus or Ōkeanós was one of the Titans who served originally as the god of the ocean. After the gods of the Greek pantheon defeated the Titans, Oceanus’ role became more as a personification of the ocean itself as well as the father of river and ocean gods and nymphs while the god Poseidon ruled the ocean itself. Oceanus was notable for being one of the few Titans who didn't fight in either of the major battles in ancient Greek lore. The relationship between Poseidon and Oceanus was similar to that of Apollo and Helios. There is no definite origin for how the name Oceanus came into the Greek language with several etymologies suggesting it was a loanword from another, possibly pre-Greek culture.

The Romans also adopted the word into Latin as oceanus, which entered into Old French as occean or océan. By 1300, the word had entered English, also with the alternate spellings of occean and ocean. What the ocean itself referred to also changed as the term did. The ancient Greeks and Romans believed that what they could access from the Mediterranean was the entirety of the ocean and believed that this was not a massive sea but rather an extremely large river that encircled the earth.

The term sea and the term ocean have been used interchangeably over the years, perhaps because of the belief of ancient European cultures in the Mediterranean that their large sea was an ocean. However, this is not strictly accurate. While there is no sharp distinction between what size makes an ocean and what size makes a sea, the term sea refers to a body of water either partially or fully enclosed by land, usually smaller bodies of water like the North Sea, Red Sea, or Dead Sea. For those not fully enclosed by land, seas themselves can often be considered smaller subjects of oceans. American English is more likely to use the term ocean and sea interchangeably, possibly because in America there is some debate over whether some of the country’s greater lakes - the Great Lakes region and the Great Salt Lake - might be more accurately described as seas.

As knowledge of the world has grown, so has how we identify oceans around the world. Depending on who you ask, there are as few as one and as many as five oceans on the planet. The concept of the “world ocean” is a new one as all of the oceans identified on the planet are connected as a continuous body of water encircling most of the earth. Outside of this theory, researchers agree to the identity of three more oceans: the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans. Of these, the Pacific is the largest while the Indian is smallest.

Debate continues over whether two additional oceans - the Southern Ocean around Antarctica and the Arctic Ocean around the Arctic region - should be considered extensions of the other three oceans or independent oceans themselves. One of the reasons researchers feel that the Southern and Arctic oceans should be separated out of the Pacific, Atlanta, and Indian oceans because the temperature differences between the Southern and Arctic regions create completely different ecosystems and a different role and impact on the planet.

A lot of the definitions of what constitutes an ocean as well as the boundaries of those oceans is generally set by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). This intergovernmental entity includes 88 member countries and its principle goals are for the surveying and charting of the oceans to allow for save navigation and trade the world over. It also sets standards for instruments used in ocean navigation. Officially established in 1921, the IHO operates out of the principality of Monaco.

REEF

A reef is any ridge or shoal of rock, coral, or similarly stable material that lies beneath the surface of a natural body of water. While the terms coral reef and reef are sometimes treated as synonymous, not all reefs are comprised of coral. While coral reefs are the most common, natural reefs also include oyster, sponge, and rocky reefs while there are artificial reefs created both intentionally and unintentionally, largely through human activity.

The term reef has its origins in the PIE root word rebh meaning “to roof, cover,” which came into Old Norse as rif. This word originally meant “rib” and was applied to mean both the reefs or ridges in the sea as well as the ridges or reefs in a sail. In fact, when the term reef - then still spelt as rif - entered the English language in the late 1300s as a reference to the horizontal section of a sail when it is rolled or folded. The rope used to tie this sail was known as the rif-rope. The use of reef meaning “low, narrow rock ridge underwater” first appeared in the 1580s with the alternate spelling as riffe.

Large colonies of oysters can come together to found oyster reefs on stone as well as hard marine debris with new, living oysters building on the older, dead oysters as the colony grows. This growth is also referred to as an oyster bed, oyster bank, oyster bottom, or oyster bar depending on the region where they are located. Overfishing, environmental degradation, and diseases have led to a decline in oyster reefs, particularly in the Chesapeake region.

Formed by sponges and their silica skeletons, sponge reefs are made of hexactinellid or glass sponges. Once, these very rare reefs were thought extinct sometime during or shortly after the Cretaceous period until existing reefs were discovered in the late 1980s. Considered living fossils, while hexactinellid sponges are found worldwide the only place where they continue to form reefs is on the western Canadian continental shelf. Also known as sponge mats, these reefs are damaged by fishing, particularly from bottom trawling and dredging techniques. Since the rediscovery of these reefs, certain types of fishing have been banned in these areas by the Canadian government.

Artificial reefs are the third kind of non-coral reefs found in the ocean. Artificial reefs are generally purpose-built by humans to promote marine life though many shipwrecks have become unintentional artificial reefs along the seafloor. Artificial reefs can be built by scuttling ships, using rubble or construct debris, or purposefully built with materials like reef balls, PVC, and concrete. Artificial reefs can be constructed for a variety of reasons including preserving marine life, controlling erosion, blocking ship passages, to improve surfing, or to to stop trawling nets from being used in areas.

Of course, coral reefs are the most commonly found reefs in underwater ecosystems and perhaps also the best known type of reef. These colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate are known as the rainforests of the sea because of the biodiversity they create. While they only occupy less than 0.1% of the world’s ocean area, coral reefs are home to at least a quarter of all marine life. Since the 1950s, the number of coral reefs on the planet have halved because they are sensitive to water conditions and increased pollution and environmental concerns have put them - and ecosystems they create - in danger. While the Great Barrier Reef is perhaps the most well-known coral reef, there are numerous reefs throughout the ocean.

There are four main types of coral reef found in the ocean though there are at least eight similar types or variants of these reefs. The fringing, barrier, and atoll reefs were originally identified by Charles Darwin but scientists have since identified other types including the platform or bank/table reef. Fringing reefs, also known as shore reefs, are directly attached to shores, often in a shallow channel or lagoon, and is the most common type of reef. One of the best developed fringing reefs on the planet can be found in the Red Sea.

An atoll reef or atoll is a circular, continuous barrier of reef that extends all the way around a lagoon on a central island, often times a volcanic island. The reef is formed as the island erodes away and sinks below sea level. The South Pacific and Indian oceans are the most common places to find atoll reefs and the large lagoons that they enclose. Some other subtypes of reefs include apron, bank, patch, and ribbon reefs as well as habili, microatoll, cays, and seamounts or guyots. Apron reefs are considered a type of fringing reef while bank reefs are considered a type of platform reef. Patch and ribbon reefs as well as cays, seamounts, and microatolls are all types of reefs associated with atoll reefs. The habili is a type of reed specific only to the Red Sea.

SALINITY

While the ocean consists of salt water, the amount of salt in that water varies depending on where in the ocean one is. The ocean’s salinity or amount of salt in a certain area can have an impact on what type of life can exist in that part of the ocean as well as plays an important role in climate and weather. In oceanography, salinity is specifically defined as the total amount of dissolved salts in seawater, though even fresh and drinking water can contain some level of salt and still be safe for consumption.

The word salinity comes into English through the words salt and its adjective form saline, both of which have the same proto-linguistic origin but came into English via different routes. Both words come from the PIE root word sal meaning salt, but the word salt came from the Proto-Germanic saltom, which was the source for the Old English sealt before coming into its modern spelling as salt. The term applied to common table salt as far back as the 1300s but it was known as an alchemical element by the 1580s and as a chemical from 1790. The word saline meanwhile went from the PIE sal to the Latin sal or salis, which was the base for Latin terms like salinae meaning “salt pits” and salinum meaning “salt cellar.”

The term saline was in use in English by the 1500s to describe things that were “made of salt,” but that use is now obsolete. Instead, the term became an adjective meaning something that pertained to or was characteristic of salt by the 1770s. By the 1650s, the suffix -ity had been applied to create the term salinity, a noun form referring to something that was salty and character or quality. The concept of saline solutions appeared around 1833.

There are four main categories of salinity in water. Fresh water is considered any water that is 0.5 parts per thousand (ppt) salt and only 2.8% of water on the planet meets this definition. Within the fresh water category is water safe for human drinking consumption, also known as potable water, which is 0.1 ppt. Water used for agricultural irrigation must be 0.2 ppt. Ponds, lakes, rivers, streams, and underwater aquifers are among the largest categories of freshwater.

The next level up is brackish water, which is considered water between 0.5 ppt and 30 ppt. Brackish water is often found in estuaries, mangrove swamps, brackish seas and lakes, and swamps - all areas that serve as transitions between inland freshwater and the ocean. Also known as brack water, this type of water is hostile to most terrestrial plant species but does house a wide variety of animal life that can exist in both fresh and salt water, known as euryhaline species. The Black and Baltic seas are two bodies of water that are defined as brackish though one of the most famous examples of brackish water is possibly the Thames estuary that stretches from Battersea and Gravesend in London where it empties into the North Sea on the coast.

Saline water is categorized as that which is 30 ppt to 50 ppt and is also known as salt water though not entirely synonymous with sea water. Saline water is further defined into water that is slightly saline, moderately saline, and highly saline. While sea water is the main type of saline water found on the planet, saltwater lakes - usually found inland - also meet this category. The Great Salt Lake, Dead Sea, Aral Sea, Caspian Sea, Lake Texoma, and Devil’s Lake are some well-known examples of salt lakes. There are some 945 salt lakes and 166 saltwater lakes found in China alone.

The saltiest type of water in terms of salinity is brine water, defined as water that is 55ppt or more. Brine water has uses for cooking and food processing, de-icing roads and structures, and other technological and industrial processes. In nature, brine water is often found underground in salt lakes or as sea water. In the ocean, brine is formed through processes of evaporation, the formation of sea ice, and salt domes. Evaporation is the most common way brine is created and can be found throughout the geologic record.

The saltiest body of water on the planet is the Gaet'ale Pond near Afar, Ethiopia, which is categorized as having a salinity of 433 ppt. By comparison, the average salinity of the ocean is only around 35 ppt. The pond is a newer body of water having been created after an earthquake in 2005 reactivated a thermal spring under the surface. The salinity of the lake has posed a danger to local residents and animals with skeletons of birds and insects being found in and around the pond.

SWASH

Anyone who has been on a beach has seen how water rushes up the sand after a wave has broken, but not everyone knows that there is a term for this water: swash. Also known as forewash, swash action is known for moving materials and sediment up and down the beach, sometimes depositing creatures and items along the beach as well as taking things from the beach out to sea. While it comes and goes in a matter of seconds, swash plays an important role in how the ocean shapes the land through accretion and erosion.

The word swash is one of uncertain origins. This word is either imitative of the sound the wave makes itself or an intensification of the verb wash. If the word wash is the origin, it can trace its etymological roots back further to the PIE root wed- meaning “water, wet,” and then through the Proto-Germanic watskan meaning “to wash” and finally the Old English wascan meaning “to wash, cleanse, bathe.” Either way, swash as a noun meaning “the fall of a heavy body or plow” as well as “pig-wash, filth, wet refuse” first appeared sometime in either the 1520s or 1530s. In the 1540s, the term swash also began to apply to a swaggering, fighting man who paid particular attention to an opponent’s shield later to evolve to the term swashbuckler in the 1550s. It was possibly the association of swashbuckling with pirates that led to the word swash becoming related to “spill or splash water about” in the 1580s and then “a body of splashing water” in the 1670s.

There are two parts or phases to swash: the uprush, also known as onshore flow, and the backwash, also known as offshore flow. The uprush phase has a higher speed but shorter duration than the backwash though the speed of the backwash increases as it ends. The direction that the swash uprushes on a beach depends on where the prevailing winds come from but the buckwash always retreats in a fashion perpendicular to the coastline.

Because swash retreats asymmetrically, it serves an important role in transporting sediment, erosion, as well as longshore drift, which is the geological process by which sediments are transported along a coast parallel to the shoreline. The process is also known as littoral drift and is one of the reasons why those who swim out in the ocean will sometimes find themselves further down the beach than where they started.

The area where swash occurs is known as the swash zone and it is this area of the ocean that is highly susceptible to human activities from property development to outdoor recreation. The coastal erosion that swash effects can cause damage to property as it reshapes beaches and coastlines. Some communities along beaches have constructed sea walls to prevent the coastal erosion of roads and buildings when the swash exceeds its regular coverage zone.

However, the construction of seawalls doesn’t retain beaches and can interfere with the natural process of the swash zone. Placing rocky debris or boulder ramparts like revetments or riprap are more natural ways of preventing beach erosion while still allowing swash to occur. As climate change continues and with 100 million people living within one meter of sea level, dealing with the changing of the ocean has become more important than ever.

TIDE

Tide is defined as the rise and fall of sea levels which is caused by gravitational forces exacted by the moon, sun, and earth’s rotation. Humans have long observed the tides and sought to understand how they work for centuries. Better understandings of gravity and physics have gotten humanity to the point that tide changes and levels can be accurately predicted. The main difference between tides and currents is that tides are the up and down motion of the wave while currents are the left and right movement of water. Both have an influence on each other.

The word tide comes from the PIE root words di-ti- meaning “division, division of time” and came into Proto-Germanic as tidi meaning “division of time.” This led to the Old English tīd meaning “point or portion of time, period, season, feast day, canonical hour.” It is this form of tide as reference to liturgical periods like Christmastide or yuletide. It wasn’t until the mid-1300s that this word began to refer to the rise and fall of the sea because of the realization that these tides were on fixed tides. The term tide especially referred to the period of the highest tidal waters. Interestingly enough, the Old English heahtid meaning “high tide” literally referred to festivals or holy days.

The aboriginal Yolngu people of what is now Australia’s Northern Territory may have been the first civilization to realize that the moon was connected to tides as they incorporated this belief into their mythology. The first written record connecting the moon to tides was an ancient Purana text from India from between 400 and 300 BCE referring to how the light of the moon corresponded with rising and falling tides. Greek philosophers realized this connection as far back as 150 BCE with figures such as Seleucus of Seleucia, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes, Aristotle Plato, and Plytheas of Massilia all exploring this theory. In ancient Rome, Pliny the Elder made reference to the link between the sun and moon with tides.

By the medieval period, it was accepted by writers like Bede and Dante that tides were linked to the lunar cycle and seasons, but no European writers or scientists tried to make any further determinations about this link. Meanwhile, Muslim astronomers were using translations of ancient works to further their own studies of the subject and their writings would later influence western though.

It was Isaac Newton’s work on gravity that really began to revolutionize tidal theory and he included his work on the subject in his Principia. It would be further explorations of the ocean based on Newton’s work that helped explain how the gravitational forces of the moon when exerted on the earth causes the ocean to expand and retract. The sun also has similar impacts and causes variations on the forces exerted by the moon. The distance of these two bodies in the solar system impacts how and when tides change.

Low and high tide are the two main stages of tides. Low tide is when water stops falling because it reaches the minimum of its function whereas high tide is where the water stops rising because it has reached its functional maximum. Between high and low tide are two other phases: flood and ebb tide. Flood tide is the period between low and high tide where the sea levels are rising and covering the intertidal zone whereas the ebb tide is when the sea level is falling and reveals the intertidal zone.

Tides are typically semi-diurnal, meaning there are two high tides and two low tides each day. Even in areas with two high tides and two low tides, one high tide will be higher than the other and one low tide will be lower than the other. This difference is less the closer the moon is to the equator. However, others are diurnal meaning there is one high tide and one low tide per day.

TRENCH

Long narrow depressions on the seafloor, ocean trenches mark not only the deepest parts of the ocean but the deepest parts of the natural world - both known and unknown. Humanity has only begun to plumb these deepest of depths with bathymetry being the study of underwater depths as it pertains to oceans, lakes, and rivers. By learning more about trenches, researchers not only find out more information about some new forms of life but also can better understand earthquakes, volcanoes, and plate tectonics.

The term trench originates possibly from the PIE root word tere meaning “cross over, pass through, overcome” but definitely from the Latin truncus meaning “maimed, mutilated” and also the trunk of a tree or body. This influenced the Latin verb truncare meaning “to maim, multiate, cut off” from which we get the word truncate. The term truncare passed into Vulgar Latin as trincare, which became the Old French trenchier meaning “to cut, survey, slice.” This is also the origin of the medeival term trencher, which were plates made of wood or hardened bread.

From trenchier also came the Old French trenche meaning “a slice, cut, gash, slash or defensive ditch.” By the 1300s, the term trench had entered English first meaning a track cut through a wood and then by the 1400s a long, narrow ditch. The first time the concept of trenches in military warfare was written about in English in the 1500s though the term trench warfare wasn’t going until World War I. It would be in 1923 that the term trench was first applied to the narrow chasms found in the ocean when the term appeared in the textbook An Introduction to Oceanography, which was written by noted Scottish biologist and oceanographer James Johnstone. The origin of this term reflects the great changes that were happening in the world and that would facilitate even more researcher deeper into the ocean.

Technological limitations prevented humanity from exploring much of the ocean until the late 1800s when the Challenger expedition between 1872 and 1876 began using sound to determine how deep the sea floor was. It was during this point that the Challenger Deep in the Mariana’s Trench - still known as the deepest point on earth - was first discovered. In the 1920s and 1930s, technology such as the gravimeter helped researchers use gravity in submarines to better determine ocean depths.

Technological advances during the Pacific theatre of World War II helped better define ocean depth. Between the 1940s and 1960s, the study of the ocean floor and trenches within the ocean really began to take off. Sonar allowed the mapping of the ocean floor while technological advancements allowing humans to make deeper dives as well as unmanned video and submersible technology helped researchers gain new awareness of what lay below.

Named for its location about 124 miles east of the Mariana Islands, the Mariana or Marianas Trench is the deepest oceanic trench on earth and runs for some 1,580 miles in length and 43 miles in width. The deepest part of this deepest trench is the Challenger Deep, so named for the Challenger expedition. Measuring at least 10,902 miles deep, this area of the earth is so deep that if Mt. Everest was placed in it, the world’s highest mountain would still be underwater by more than two miles. Because of the intense depth and pressure, few manned missions to the Challenger Deep have ever been made with only 22 people having descended it.

Trenches are located in what is known as the hadal or hadopelagic zone, a reference to Hades, the Greek god of the underworld. These depths of in excess of 6,000 meters or 12,000 feet are among the least explored marine ecosystems and their lack of sunlight and nutrients, high pressure, and low temperatures make them home to creatures that are found - and possibly could survive - nowhere else on the planet. Sea cucumber, bristle worms, bivalves, isopods, sea anemones, amphipods, copepods, decapod crustaceans, and gastropods are known to make their homes here as do simple-celled organisms and a small number of fish species like grenadiers, cutthroat eels, pearlfish, cusk-eels, snailfish, and eelpouts. The cuskeel currently holds the record as the fish known to have the deepest habitat.

WAVE

The term wave has numerous applications from sound waves to surface waves to gravitational waves and standing waves. A wave is generally defined as some sort of dynamic disturbance that changes equilibrium in some fashion. What we know as an ocean wave is perhaps better defined as a wind wave or wind-generate wave, a type of water surface wave that results from winds blowing over the surface of an ocean. These waves can travel thousands of miles before reaching land but can also range in size from small ripples to those over 100 feet in height.

The word wave is rooted in the PIE term wegh- meaning “to go, move” and then Proto-Germanic as wag- meaning water in motion, wave, billow.” From this it became the Old English wagian meaning “to move to and fro” and its verb form wafian meaning “to wave, fluctuate”. Meanwhile the Old English term for “a moving billow of water” was yð. The Old English wagian became the Middle English waw before becoming the verb wave. The noun form didn’t change from wagian to wave until the 1520s to match with its verb tense.

There are five factors that influence how waves are formed in the ocean: wind speed or strength, the distance over open water in which that wind blows (known as fetch), the width of the area where the wind contacts the water, the wind duration, and the water depth. These factors working together determine the wave’s height, length, time interval between crests, and direction.

There are three different types of wind waves that develop in the ocean over time. Capillary waves or ripples are dominated by surface tension while gravity waves are dominated by gravity. Swells have traveled away from where they were originally raised and are also known as surface gravity waves. So-called rogue waves, also known as freak, monster, killer, or king waves, occur at much higher than most waves and are unusually large and unpredictable but not as large as tsunamis.

A wave is said to be “breaking” when its base can no longer support its top, causing the wave to collapse. This often happens when the wave comes into shallow waters or when two wave systems collide. Breaking waves are divided into three categories as well. Spilling or rolling waves are the safest areas in which to surf and happen along relatively flat shorelines. Plunging or dumping breaks are ones that can push swimmers or surfers to the bottom with great force and preferred by more experienced surfers. Surging waves may never break and have deep water below them. This type of wave can drag those in the water deeper into the water, making it hard to return to the shore.

While it may seem like rogue waves produce the biggest waves, the biggest wave on record was actually an open-water wave recorded in 2013 in the North Atlantic and measuring some 62.3 feet or 19 meters. The most extreme rogue wave was only 58 feet or 17.6 meters and was recorded near British Columbia in 2020. The largest artificial wave ever generated by humans was created at the Delta Flume wave generator in the Netherlands which reached a maximum height of 16.4 feet or 5 meters.